One of the first things a writer does when starting a new story is choose a point of view. This important step should be done with intention, as point of view greatly affects how readers experience a story.

When the author isn’t intentional about the point of view they choose, or when they aren’t consistent with it, their readers will notice that something is off. Readers may not be able to pin down exactly what the issue is, but they will feel it.

This blog post explains the basics of point of view. There’s a lot to learn, but knowing a few key concepts will take you far.

Let’s get some concepts defined first

The narrator. The narrator tells the story. They are either a character in the story or someone observing the characters in the story.

The author. The author decides who the narrator is and what kind of personality or voice they have.

Point of view. The point of view is the perspective from which a story is told—first person, second person, or a type of third person.

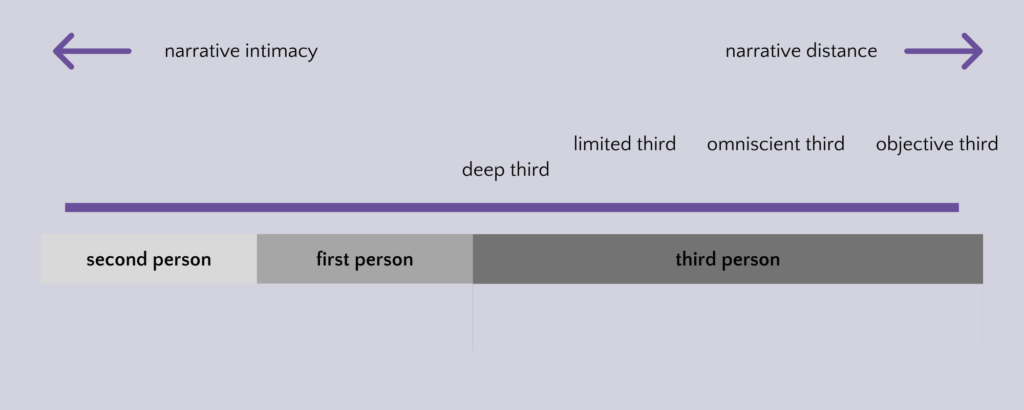

Narrative distance. Narrative distance is how close readers feel to the characters and events in a story. Actually, it’s how far the narrator is from the characters and events, but in the end, the readers are the ones who will feel the intimacy or distance. How much of the point-of-view character’s mind do readers get to experience?

Authors use narrative distance like a zoom lens. Zoomed way in, readers are right there, experiencing the story’s events from inside a character’s head. Zoomed way out, readers are aware of only the characters’ dialogue and actions.

The narrative distance can be altered slightly at various points throughout the story, especially at the beginning or end of a scene or chapter. However, for the most part, your narrative distance should remain steady. When you do zoom in or out, you’ll want to do it slowly.

The point-of-view spectrum. The various POVs exist on a spectrum of narrative distance. Certain POVs are more intimate or distant than others.

Now let’s talk about each of the most common POVs.

Second person

Second-person point of view is the least common of the common. The narrator uses the pronoun you because the reader becomes a character in the story. This is the shortest possible narrative distance.

You’re trying to make your way through the dark house without hyperventilating. You have to get to that gun. Fast.

Writing in a second-person POV can be risky. Your reader may not want to be the character you’ve created. If the character is unlikable or the events of the story too disturbing, the narrative distance can feel too short and turn your reader off.

First person

First-person point of view is only slightly more distant than second. The narrator is a character in the story (but not you) and uses I and me pronouns.

The lights flickered on, and I gasped. There she was, and she already had my gun. Damn. She sneered at me. I’d play it cool.

First person can work well when your main character has a captivating personality, because your reader gets to be inside the character’s head, knowing exactly what they’re feeling and thinking.

First-person stories can make for exciting reads. The reader isn’t told anything that the POV character doesn’t know, which means the reader can easily become immersed in the story.

Third person

In third-person point of view, the narrator uses he, she, they pronouns. Various third-person POVs exist; I’ve seen some long lists! Here are the most common:

Limited third person. Readers are limited to the knowledge of the POV character in limited third person. But there’s more distance between them and the POV character.

The author creates this distance by using a narrator that isn’t a character in the story. And the narrator uses neutral language that doesn’t usually reflect the POV character’s personality. More filters will be used in limited third POV than in first-person or deep third-person POV.

The lights flickered on, and he gasped. He saw her standing there with his gun in her hands. She sneered at him, and he decided to act calm.

Deep (close) third person. A subcategory of limited third is deep third person, where the narrator is definitely a character in the story. Like a first-person POV story, a deep third-person story can be a riveting read because readers are close to the character and the action, and they know only what the POV character knows. The narrative distance is short (or close).

The narrative in a deep third-person story is told using language the POV character would use. Readers are getting the story filtered through the POV character’s personality.

Avoiding or decreasing the use of filters (e.g., she heard, they knew, he felt, etc.) is another way the narrative distance is shortened.

The lights flickered on, and he gasped. There she was. Damn, she already had his gun. Ugh, that sneer on her face. He’d play it cool.

Omniscient third person. The narrators of omniscient third-person stories have their own personalities and opinions, and often make their own judgments about the characters, but are not usually characters themselves (unless they are something like a god).

These narrators are all-knowing, so readers have access to the thoughts and feelings of many characters. However, the story is filtered not through the characters’ personalities but through the strong personality of the narrator.

Because the story is filtered through the narrator’s personality, the language used to describe the various characters’ thoughts and feelings remains consistent throughout the story. It’s not neutral (because the narrator has their own opinions), but it should carry the same tone throughout the book.

The lights flickered on, and he gasped. He saw her standing there with his gun already in her hands. But James was not a man who panicked, even when a circumstance seemed hopeless. He remained still and waited for her to speak.

Feeling more powerful than ever, Lana allowed an ugly sneer to cross her face.

Neither of them knew that the gun was empty of bullets.

Objective third person. The narrator of an objective third-person story has no access to the characters’ thoughts and feelings. So, readers must pick up clues from the characters’ behavior and dialogue.

The lights flickered on, and he gasped. She stood in a corner of the room, with a gun in her hands. She sneered at him, but his face showed no emotion.

Writing in objective third is like screenwriting in that the author tells only what can be seen in observation, or what could be seen on a screen. This POV is the most distant. The downside to that distance is a lack of connection between readers and the characters.

Is one point of view better than the others?

No, but a particular point of view might be better for your story.

Which point of view you choose will depend on your story’s genre, your writing style, the story line, and current trends.

Current trends favor a close narrative distance (e.g., deep third person or first person). Many of today’s readers just happen to relish falling deep into characters’ minds. But that doesn’t mean you can’t have success with another POV.

Readers also have expectations based on a book’s genre.

- Romance usually uses first- or third-person POV, often alternating POV characters with chapters.

- Diary-style novels are written in first person.

- Mysteries and thrillers work well in first person or limited third, especially deep third.

- Family sagas are often written in omniscient or multiple limited third-person POV.

- Magical realism is often written in omniscient third person.

- Historical fiction, science fiction, and fantasy can be written in limited third person, first person, or omniscient, depending on the cast of characters, the number of setting locations, and the number of years the story spans.

Researching successful novels in your genre can give you an idea of which point of view might be best for your story.

What matters most is that you correctly use whichever POV you choose. I’m not usually one to advocate for blind rule-following, but POV rules are crucial to learn and apply.

Some POV rules to follow

If you’re writing in first-person or deep third-person POV, you’ll want your narrator to use words your POV character would use. What happens in the story is filtered through your POV character’s personality and background. Writing in this way will help to further limit that distance between the reader and the POV character, which is the goal of deep point of view.

If you have multiple POV characters, make sure they each have their own unique voice. You want your readers to know at the beginning of a chapter or scene whose viewpoint they’re reading. And you don’t want your readers to have to go back and check the chapter heading to remember which character’s POV is the current one; it should be obvious.

Make sure your POV character doesn’t know things they shouldn’t. If you’re writing in single limited third person, and Karli is the POV character, readers can’t know that Karli’s son carried a can of beer behind her back and into his room unless his little brother tattles on him, or Karli later finds the empty can.

Stay consistent. Keep with the point of view you chose for your story throughout the book. You might increase or decrease the narrative distance a bit at the beginning or end of a chapter or scene, but completely changing the POV randomly throughout your novel will leave your readers’ heads spinning.

Don’t switch POV characters midscene. Unless you’re writing in omniscient third, don’t give the readers two different characters’ thoughts in one scene. Stick with one POV character per scene.

This brings us to the topic of head-hopping.

Head-hopping

When your point-of-view character changes midscene, and especially when the thoughts and feelings of multiple characters are shared midparagraph, you are head-hopping. Readers are suddenly experiencing the scene from a completely different viewpoint, through a whole different character’s personality.

Very few authors can pull this off without confusing or annoying their readers.

Omniscient third-person point of view does often include multiple characters’ POVs within a scene. However, omniscient also requires an all-knowing, opinionated narrator who probably isn’t a character in the story. If you choose to hop into the heads of multiple characters in a scene without deliberately setting up a well-developed omniscient narrator for your story, you’re head-hopping. Avoid head-hopping.

Other resources

If you’d like to learn more about establishing and maintaining a point of view that will satisfy your readers, I recommend reading the following:

- Point of View by Sandra Gerth

- “Verifying Viewpoint: Affirming Point of View” from The Magic of Fiction by Beth Hill

- “Point of View” from Self-Editing for Fiction Writers by Renni Browne & Dave King

Get in touch with a developmental editor or book coach for help with choosing or establishing the best point of view for your story.

Then, during your manuscript’s final edits, find a line editor or copyeditor who can check your scenes for spots where you’ve deviated from your chosen POV or changed the narrative distance too quickly. This is something I do for my clients, so if you think you’re ready for this stage of editing, fill out my inquiry form to receive a free sample edit and learn more about working with me.

Pingback: Mind Your Verbs - LaBine Editorial

Pingback: Cutting the Unnecessary from Your Manuscript - LaBine Editorial

Pingback: Rules and Fiction Writing - LaBine Editorial